Bronwyn Williams-Ellis is the great niece of Sir Clough Williams-Ellis the giant of Welsh architecture, who needs no introduction.

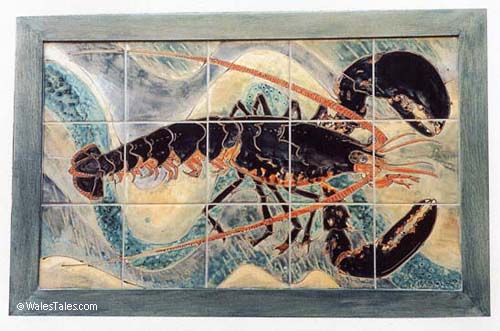

Bronwyn is also an artist, choosing architectural and sculptural ceramics as her medium. She is influenced by the sense of line and pattern, natural textures and she focuses on apparently simple things or presents things in such a way that they are approachable. This is evident in her work. Her images include swimming bodies trailing bubbles, moon faces, birds in flight, fish, daisies, seashells, wheels, gryphons, dragons and mermen.

Her work appears on private walls all over the UK, and in such public places as Portmeirion; Ysbyty Glan Clwyd in St. Asaph; the Orthopaedic Recovery Room at Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton; and the shopping centre in Cwmbran, Gwent.

Born in Burton-on-Trent of Welsh parents, her father was Sir Clough’s brother Martyn, Bronwyn’s youth and young adulthood were spent in Northern Ireland and in North Wales. Bronwyn has happy memories of the times visiting at Plas Brondanw, remembering Clough and his wife, Amabel; both of whom she calls “formidable”, meaning that they were big people with a presence that must have felt like rolling thunder to a child.

“Oh, they were like giants when I was a child” she says, “bellowing to each other across the house – and I couldn’t understand a word they were saying, they were so loud. They were so tall, Clough had the longest shanks I’d ever seen; the rest of us were really in the basement.”

Stories about Clough Williams-Ellis tumble joyfully from her. Yes, she wishes he were still here; that she could have been older when she knew him so she could ask him questions. Although, when Clough talked, people generally listened (“You didn’t question him”).

Part of his quirk, however, was to act like a dilettante in Portmeirion and around architecture, delighting in frustrating his secretaries, like Richard Haslam, who compiled a book on Clough’s architecture. Clough wouldn’t give the reasons for his buildings. They stood for themselves.

When Clough and Amabel got married his regiment asked what he wanted for a gift, silver, they suggested. He said he wanted stones. From these stones he built at Brondanw his folly tower, which was then mistaken to be a 14th century construction by visiting experts.

An aside: Clough’s interest in architecture may have been influenced by his mother’s drawings. “Looking at her drawings”, says Bronwyn. “There are beautifully drawn houses that look like the ones Clough designed. Clough even titled his drawings in a style similar to hers. They were an intelligent family.”

While Clough was influenced by his mother, it appears he influenced many women himself. Bronwyn recalls, “One day, after Clough’s passing, Amabel and I were having tea in the garden at Brondanw, and suddenly Amabel looked up and hissed ‘Oh, here comes another one of those women. She’ll want to talk about Clough!’ Amabel, from a literary background and an author of several books, may have thought people didn’t consider her work as important as Clough’s.”

Continuing the Williams-Ellis line, Bronwyn has left her personal signature on Portmeirion. She designed the large tile work murals above the sinks in both the ladies’ and the gents’ at the hotel restaurant.

In the Village she made the green and white foliate clay panel, at Clough’s request, which is on the back of the Gothic Porches. She laughs warmly at the memory as she notes that she misspelled Portmeirion on the panel, but she doesn’t think Clough minded. The process involved in making this panel meant engraving letters on a plaster slab in reverse. This is likely why the spelling error occurred.

She also painted the panels that go in front of the Hercules Hall thatched roof bar when it is closed. “It’s a false front on board, just a doodle really.”

Walking around in Portmeirion with Bronwyn is a pleasure as she points out one of her favorite spots: the corner in Battery Square formed by Toll House meeting Battery Cottage. These are linked with an arch; a tree grows gracefully just to the side of that arch; and a stone woman’s face looks on from the Toll House wall.

She also points out how lip of the roof of Neptune was molded into curved above some of its windows to give the windows an arched look. What is her absolutely favorite bit of Portmeirion? “As I grow older, always something I see anew.”

Moreover, she sometimes notes items that have vanished. One such piece is the reclining mermaid that graced a narrow ledge on the village-side of the shell grotto. The mermaid may have been the work of Susan Williams-Ellis. The photo is kindly provided by Bronwyn.

Robin Llywelyn, Portmeirion's managing director, adds, "We have the mermaid now restored and ready to go back. We will leave her in the original sandstone [as she appears in the photo] rather than paint her with gloss paint. The Neptune plaque is similar to the one on Neptune cottage. I'm not sure what happened to this; this must be quite an old photo. Hopefully, we will have a replica made to go with the mermaid."

Once noted for her swimmer, pool and cool water influenced glazed images, Bronwyn is now developing a series of works influenced by the earth.

“I’ve been making a lot of tiles and clay panels in recent years with a watery theme using Arabic/Russian high alkali glazes producing rich turquoises and blues. A change has set in and I’m experimenting with a new group of pieces and tiles using earth colors, rich terra cottas. Some abstract and related to landscape and geology, and some figurative relating to archeology and history. Like Clough, I’m interested in the impact of intense color.”

Bronwyn currently lives and works in Bath.

# # #

Responsive HTML Retina Ready Bootstrap Goodness

Responsive HTML Retina Ready Bootstrap Goodness